Geology, mines and quarries - page 6

A note on transport

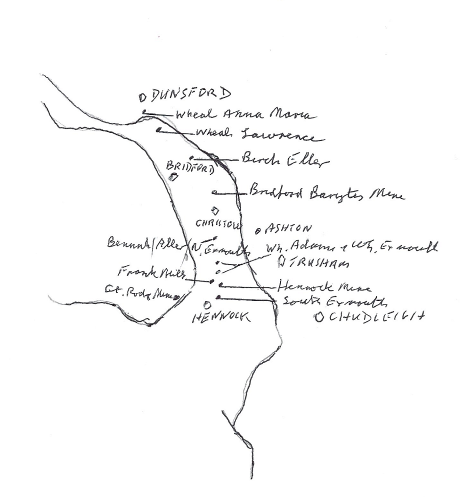

One difficulty under which the Teign Valley mines laboured was in getting the ores to their markets. The Tamar mines had close access to a number of quays on the estuary, from Morwellham (which could accommodate vessels of 300 tons) southward. Whether making for Exeter or the Teign estuary it was lengthy journey by horse and cart with loads a fraction of what could be carried by water. According to the Revd. Carrington wheeled vehicles weren’t seen in Bridford until 1820, packhorses and sledges being more appropriate to the conditions. The first edition Ordnance Survey map of 1808 shows no direct route along the Teign Valley, but the establishment of the Tedburn to Chudleigh turnpike trust in 1831 would have somewhat eased the situation.

The opening of the Teign Valley Railway from Heathfield to Teign House Siding in 1882 came too late to aid the lead mines, although it was to be of great benefit to Trusham Quarry. The eventual completion of the route through to Exeter in 1903 was advantageous to the barytes mine and made feasible the marketing of stone from Bridford and Scatter Rock quarries.

Building materials

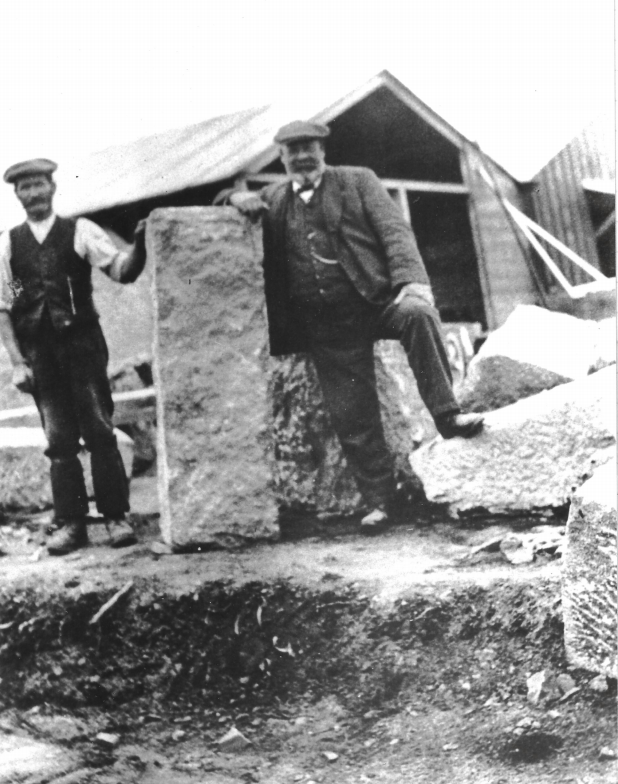

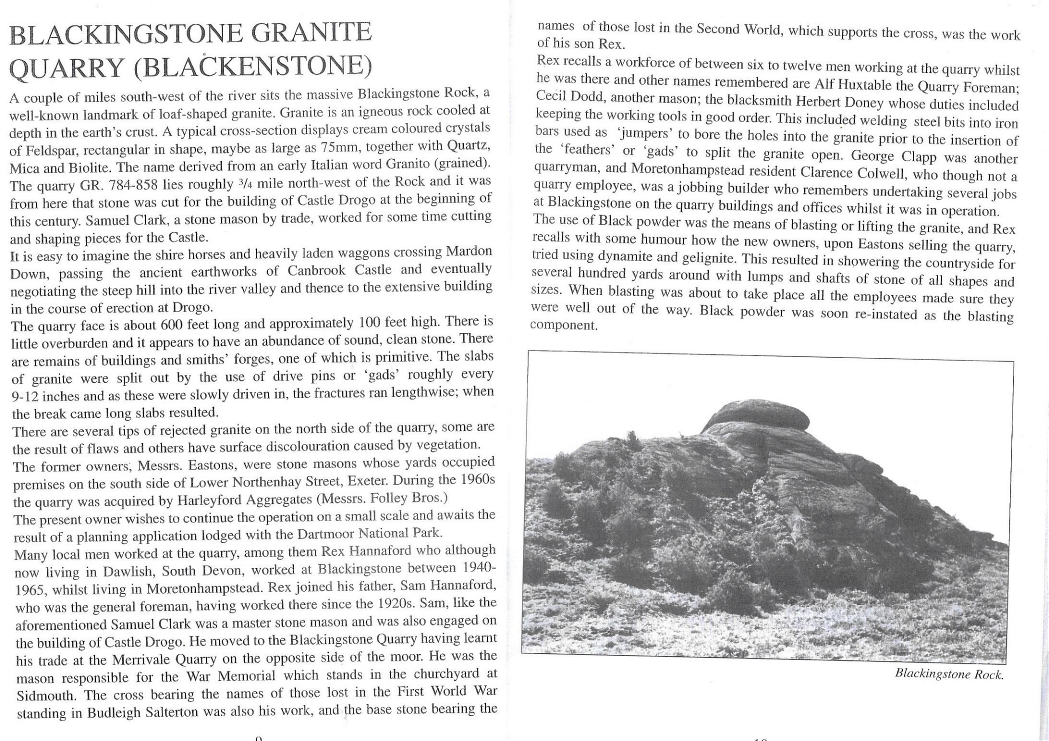

Any granite used in Teign Valley houses before the nineteenth century was (literally) moorstone, gathered from the surface and then cut and dressed for use. The earliest Dartmoor granite quarries were at Foggintor (Princetown) and Haytor, active from the early 1800s. Our nearest such quarry, Blackingstone in the far west of Bridford parish, was one of the sources for Castle Drogo, built between 1910 and 1930.

The quarry closed in 1969 but was reopened in a small way in 1990 by Leo van Lewin and is now the only working granite quarry within Dartmoor National Park.

By far the greatest proportion of stone in the walls of Valley houses and gardens is not granite. Much of it is hard metamorphosed rock from the aureole of the granite plateau, the rest being such unaltered local chert and other stone as proved suitable for the purpose. A great deal of all this, especially the unyielding metamorphic ‘woodstone’ or elvan, must also have been stone cleared from fields. However, given the amount that has been put to use over the years it is hard to believe that some of it wasn’t derived from excavation. In districts where stone was the preferred material for walling it sometimes came from small and very local quarries which might be opened for one project – a substantial house and its outbuildings for instance. The less transport it needed, so much the better. There may be small quarries of this sort locally, especially away from the foot of the escarpment and to the east of the river where there is little useful surface stone, but if so, they are neither documented nor marked on maps. Cob too might be expected to leave some trace of diggings, especially where the subsoil used was of good depth above the underlying bedrock. The size of hole required to put up even a modest stretch of cob wall is surprising. Some of the material used may have been redeployed spoil from the site-work – this is easy to envisage where a house or barn is built into sloping ground. There are three large pits in Christow parish, not for cob but for the clay used in the construction of the reservoir dams. Two of these, now ponds, at Court Barton and a third is at Heckland Farm, up Commons Hill, and until 1970 used as a refuse tip by the district council. Perhaps the supply of Heckland clay was limited or its quality inferior, otherwise the builders would hardly have chosen an alternative source at the bottom of Commons Hill with the challenging transportation which that entailed.