Geology, mines and quarries - page 4

Prosperity at last

Wheal Adams produced 328 ton of lead in 1849, giving its investors something to celebrate after four or five unprofitable years, but the continuing problems of soft ground and the erratic nature of the deposits encouraged a shift of focus to the southern extension of the lodes. Obtaining a lease from the Canonteign estate, the same company opened a new mine in 1851. This was Wheal Exmouth, named for the viscounts, its buildings unmissable beside the high road passing Canonteign and its spoil heaps equally obvious on either side of the valley road below the golf club entrance. The already faltering production of the former mine was subsumed within it in 1853.

By 1856 Wheal Exmouth’s Porter Shaft had reached 85 fathoms. This was next to the engine house, built in 1853, described then as “probably the handsomest building of its kind in England” and in the 1990s converted from its ruinous state into a handsome residence. The labour force of 150 was now generating a profit of £200 a month, raising useful amounts of zinc ore as well as lead and silver. In 1859 17 tons of copper were sold – the only sale of this valuable ore recorded from the Teign Valley. No more than a token perhaps, but sufficient to generate a good deal of optimism - for these were the glory days of Devon Great Consuls in the Tamar Valley, at that time the world’s greatest and most profitable copper mine, and there could always be hope that the Teign Valley too could be the maker of fortunes. In this spirit the old mine at Aller was revived in that same year, but failure to locate fresh ores and the collapse of the shaft put paid to this venture which closed after little more than twelve months.

Hennock interlude

Meanwhile a further attempt was being made to find profitable deposits of ores at the old Wheal Prosperous site, on Franklands Farm just south of the Beadon Brook, which had closed in 1840. The Hennock Silver-Lead Mining Co. started operations here in 1849 having appointed the manager of the old mine, Captain James, to be in charge of this new venture. He created a sensation at one of the company’s first meetings by condemning its prospects “on account of the leanness of the lodes”. He was shouted down and other experts called in who were able to give a more optimistic report. Despite this James was retained as manager – presumably, his actual experience of the workings was felt to override his pessimism – until being replaced by Captain Rickard, a good Cornish name, in 1852. By that year work at 40 fathoms required the expensive purchase of a 50 inch cylinder steam engine from a foundry at Tavistock, which then had to be shipped via the Tavistock canal to Morwellham, down the Tamar and up the Teign to Newton Abbot, thence by wagon to Hennock. At 50 fathoms the continuing problems of drainage and poor ventilation, and the ever present risk of workings collapsing on account of soft ground, were not compensated for by ores raised – Captain James had been right all along. In 1853 output amounted to just 29 ton of lead and 36 oz. silver. In 1855 the mine closed amidst disputes with the Palk estate over loss of water supply and damage to adjacent farmland. Prospects had seemed more hopeful a short distance to the south. Here, between what is now Teign Village and Hennock itself, a new mine was opened in 1861 under the name South Exmouth. It was soon giving employment to 122 people, 70 of them below ground. At first there was cause for optimism with rich ores at shallow depth, but this success was not repeated at lower levels. In 1865 work was being undertaken at 90 fathoms, but in 1866 output was almost nil and the operation was wound up in 1867.

The last silver-lead

Wheal Exmouth was wound up in 1862, its considerable profitability having proved to be short-lived as new levels brought into play turned out to be hardly worth exploiting while its steam engine struggled to pump out 300 gallons of water a minute. Further attempts were made here, mostly reworking previous levels and the spoil heaps, between 1863 and 1868 with a labour force of about 50 (including women and boys for the surface work) and again between 1870 and 1874 with less than 20 employees.

The last and most successful of the valley’s silver-lead mines was Frank Mills, an extension of Wheal Exmouth for which the same company had been granted a lease by the Canonteign Estate in 1853. By 1857 it was down to 84 fathoms and before its life was over had penetrated to 175 fathoms – well over a thousand feet, about 800 of them below sea level. In 1863 it employed 139 all told (89 underground) rising to 190 in 1871. In 1860 it outdid Wheal Exmouth’s production of lead (767 T to 629 T) and as one mine failed so the fortunes of the other increased. It did have to cope with flooding when ill-advised workings too close to the surface resulted in a leak in Lord Exmouth’s pond, which emptied itself into the workings. The hole was plugged quite speedily and the pond, or small lake, is still to be seen at the foot of the falls. The mine’s best year was 1865. Thereafter work at deeper levels became increasingly expensive and the deposits of lesser value. The mine is said by Schmitz to have used 130 to 140 tons of coal each week, for pumping, motive power and ore crushing. In the 1870s a boom in industry as a whole inflated the national demand for coal, and its price. The price of coal did stabilise, but by the late 1870s came the greatest threat of all – a rising tide of imported lead at prices below the cost of home production. There came a final wet winter of expensive hold-ups and remedial work due to flooding, and in 1880 the mine closed.

Barytes comes into its own

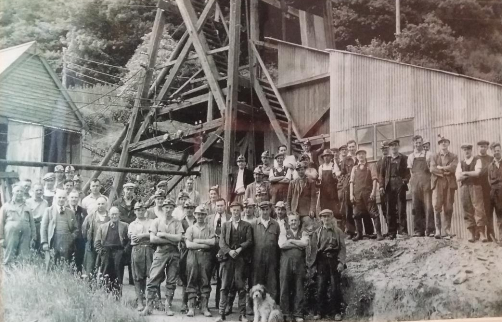

That was the end of silver-lead mining in the Teign Valley, though not quite the end of mining in the silver-lead zone. All the mines had revealed deposits of barytes but there had been little or no industrial demand for it. This situation was changing by the last quarter of the 19th century and in 1875 the mine that had shown the greatest wealth of this material – Bridford Consols – was reopened by the Teign Valley Barytes Mining Co. as Bridford Barytes Mine. There had been a previous reopening for both lead and barytes in 1870, but this had failed after two years. In its first full year the new company sold 682 T of barytes for £558 7s. 9p. Thereafter production was about 1,000 T p.a. rising to 3,000T by 1920. Most of the barytes raised before the 1920s came from surface workings. The remains of the biggest of these are visible cut into the slope a short way along Stone Lane from its junction with Pound Lane. The partly processed mineral was at first carted by road to Exeter Quay for milling. After the Teign Valley line was opened in 1882 the ore was loaded onto railway waggons at the then terminus of Teign House Siding and transported by way of Heathfield, where for the first ten years it had to be reloaded due to the change of track gauge, and so on to Exeter. Once the line was opened through to Exeter in 1903 transport was simplified.