Geology, mines and quarries - page 5

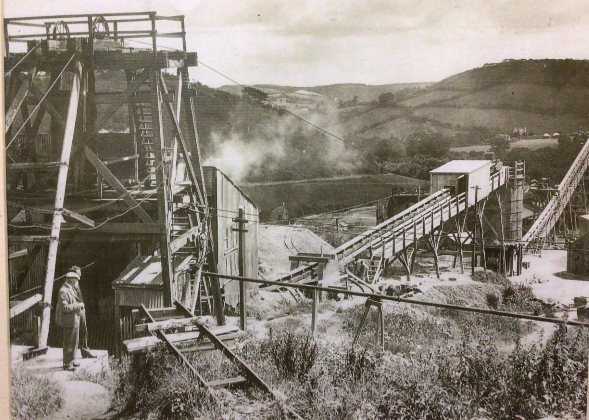

After the Great War, the mine’s future was threatened when the market was weakened by the resumption of imports and then by recession. In 1927 its owners sold it to the Shropshire-based Malehurst Barytes Co., which had direct or indirect control of several other barytes mines in the UK. Radical modernisation followed, exploration intensified, and production increased. A mill was constructed at the mine itself so that all the stages of processing the ore could be carried out there, the final product tailored to the requirement of the purchaser. A new shaft was sunk in 1929, eventually reaching below 60 fathoms.

This new investment coupled with careful management enabled the mine to survive the depression. Driven by wartime demand production reached its all–time peak of 26,000T in 1941. In 1950, when the mine had 62 employees (25 above ground and 37 below), Malehurst was taken over by Laporte Chemicals. This change of ownership again resulted in increased activity, the shaft reaching its final depth of 100 fathoms – 600 feet, 300 of them below sea level. There was some optimism that the new deeper levels would be able to replace production from the nearly exhausted upper level, but the veins of barytes were narrower and the ore of lesser quality. Then in 1954 the manager, Mr J. Stewart, was killed by a rock-fall, an accident that led to increasing concerns about the condition of the shaft and workings. These problems allied to (yet another) slump in demand led to Laporte’s decision to close the mine and thus to the layoff of the 40 strong workforce in June 1958.

Further reading from the archive: 'MINING – THE BRIDFORD BARYTES MINE'(opens on a new page)

During its life of more than eighty years Bridford Barytes Mine produced over 420,000 tons of barytes. It remains by some distance the biggest mining site in the valley, with the greatest extent of contaminated land as its legacy. ‘For what?’ you may ask. Barytes’ best-known use is probably as a constituent of the lubricating mud used in rock drilling where its density acts as a seal against upward pressure. Seemingly the skimping on barytes was a factor in the Deep Water Horizon oil rig disaster of 2010, the effects of which remain catastrophic to the ecology of Gulf of Mexico. Barytes is also used as a filler in papermaking, as a fire-retardant coating and as a spark suppressor in munitions factories. Other uses include as an extender in paint and in the manufacture of glass and cosmetics. In the form of barium sulphate, it is the essential constituent of soil pH testing solutions and in medicine is used to coat the oesophagus, intestines etc. so as to aid diagnosis in CT scans.

As to recognising it on the ground – lumps of barytes are dirty white in colour and otherwise nondescript, unless that is you pick one up, in which case you’ll be struck by its unexpected weight (twice that of quartz). Barytes itself is inert and non-toxic. The problem minerals that find their way into the Teign and which most concern the Environment Agency are zinc and cadmium, with lead also at issue. Half of the loading of these as measured at Chudleigh Bridge can be traced back to two sources – Bridford Barytes Mine and Wheal Exmouth.

What is most striking about the Teign Valley’s mining history is the proportion of ventures that ended in failure, producing little or nothing to set against the investment required in acquiring a lease, setting up a company, engaging and paying for skilled labour and covering the capital costs of sinking shafts and establishing the surface works necessary to service activity at depth and deal with the minerals once raised. Some mines, notably Frank Mills and Wheal Exmouth, were able to pay their shareholders dividends within a couple of years. Others, like Wheal Adams, needed faith to be held without reward for four or more years and then after two or three years of profit ran out of luck or out of ore. Still more were failures pure and simple. Compared to the wealth generated by some of the contemporary Tamar Valley mines our valley was an also-ran. William Morris’ father invested heavily in Devon Great Consols and did very well by it – his 272 £1 shares (a quarter of the total) being soon worth £800 each. How ironic that his son’s mediaevalising and rejection of the Industrial Revolution was founded on wealth partly derived from one of that revolution’s most toxic manifestations. But obviously some money could be made here too, otherwise the history would not be as long and as complex as it is. No doubt some promoters made a small fortune on the backs of gullible investors, and no doubt some investors did very well by off-loading their holdings at the opportune moment. The landowners could hardly lose – at any rate, the Exmouths benefited from royalties of £45,000 to £50,000 over thirty years, equivalent now to £2.5 million or more, an income approaching £100,000 a year. They were also able to enforce the preservation of their parkland and the adoption of a suitably baronial style for surface structures on their land.

The labourers at the surface and the miners, skilled Cornishmen for the most part, had no such agency. They were at the mercy of a buried geology of barely imaginable age, of an unreliable market and of the pockets of the shareholders. It’s true that as one mine failed another might prosper and provide continuing employment, but the workforce also had to hope to retain its health and physical strength, and in all too many cases miners suffered the shortened life-expectancy resulting from daily exposure to poor air and mineral dusts. Even now some memory is preserved in Valley families of forebears whose lungs were crippled by their years working at the barytes mine. There is an everyday human story here, bits of which can be got at by diligent research in the archives – as Graham Thompson shows in his book ‘A Devon Village – Christow in Victorian Times’. In this he provides much information on who the miners were – where they came from, how much they earned, where they moved to once the mining declined and a good deal of insight into their social life. The statistics show that in all the villages of the valley the population rose steadily in the first decades of the 19th century before tending to fall back towards its end, and that in Christow and Hennock, and to a lesser extent Bridford and Dunsford, there was a particularly steep increase from the 1840s - numbers peaking at the 1861 census and declining markedly between 1871 and 1881. Christow’s decline was especially precipitous – 941 in 1861, 872 ten years later and then 588 in 1881.

In the end it can be seen that the Teign Valley’s mining episode was a small and aberrant part of the Valley’s history. At the time it had great consequences in the influx of workers and capital from outside the district with all the changes this brought to the social and material life of the valley villages and to Christow especially. Now it is dead and largely buried and its sites often enough converted into desirable residences. We can assume though that there is still plenty of barytes, at least, beneath the ground, and can’t be certain that it will now be left alone for ever.