Geology, mines and quarries - page 8

Scatter Rock

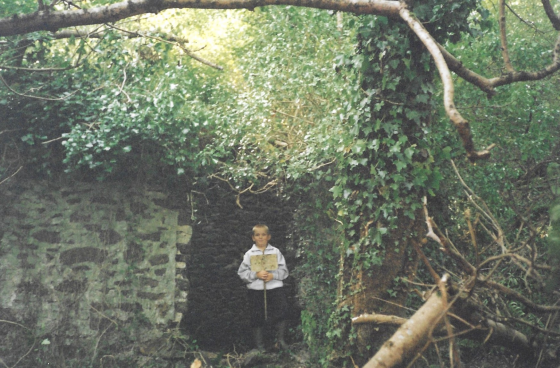

This was also known as Christow Quarry, although almost all of it is within Bridford parish. It’s said that the wearing parts of the crushers at Scatter Rock needed replacement twice as often as those at Trusham. The company set up to operate this quarry – Scatter Rock Macadams – used the hardness of the stone as its unique selling point. Their railway trucks proudly bore the slogan – “The Hardest Stone in the West”. But it was the hardness of the metamorphosed rock that led to the quarry’s decline when it was realised that its tendency to take a polish, rather than present a more gritty texture to wheeled traffic, made it unsuitable for modern road surfaces. This is the stone known variously as basalt, blue elvan, woodstone and hornfels diabase – this latter combining the German word for horn-like with an alternative term for dolerite. The floor of the original quarry is approached on the level by way of the bridge crossing the Rookery Brook beside the Christow to Bridford road, about halfway up the cleave.

JH Dickson of Bridford Quarry had been the contractor’s engineer for the construction of the Exeter Railway. This neighbouring and rival operation was promoted by directors of that rail company, most prominent among them John Dickson, JH’s uncle. The greater capital that Scatter Rock Macadams was able to draw on is shown by the fact that although the company was formed in 1911 production was not begun until 1914, by which time a direct link between quarry and railway line was in place. This was the overhead ropeway which relied on gravity – the weight of the full buckets travelling down to the station pulling the empties back up (though it was later found necessary to install an auxiliary electric motor to counteract friction). Built by the German firm Bleighert it ran for just over a mile from the crushers, above the road from Christow to Bridford at the point where it meets the brook, and into the far side of Christow Station. It was carried by two especially strong standards where its course made an angle, and by eight ordinary standards – one down in the dip beside the brook at Stone Farm being 70 feet tall, but the others of lesser height. These were constructed on concrete bases, the standards themselves being originally of timber but later replaced by steel. The site of one angle station on Southwood Farm can be seen from the public footpath, along with two of the concrete bases on neighbouring Northwood. The crossing of the two public roads and of the rail track were protected by cage-work ‘bridges’. The ropeway carried eighty buckets, each of 6 cwt (300kg.) capacity, allowing the system to transport 350 to 400 tons during one eight-hour shift.

Scatter Rock’s production in its first year equalled that of Bridford Quarry and soon exceeded it. In 1920 the upper quarry was opened at 900+ feet beside Scatter Rock (or Skat Tor) on the Christow-Bridford boundary.( 20-Min-Tei-Pho-00738) This was linked to the crushers below by a two-foot gauge tramway including an incline 460 yards (422 m.) in length – in human terms, a stiff climb (or descent).Trade fell off somewhat in the 1930s due to the problem of excessive hardness, but the 1939-45 war was a great stimulus to demand, the stone being used for airfields and other military installations. (20-Min-Bri-Pho-00265)This brought an exotic flavour to life in Christow, and an even noisier one. As well as the sound of blasting and the creaking of the ropeway the village air now sounded to the double-declutching and grinding of gears as US army GIs drove some of the stone directly away from the quarry in 6-wheeler Chevrolet trucks, a one-way system being instituted in the village to aid the flow of traffic. Here as elsewhere locals were taken aback at the racial segregation evident in the American forces.

The quarry shut in February 1950. This was not in time to save Skat Tor, the easternmost tor on Dartmoor. Sometime after the war it was blasted out of existence to be, as Stafford Clark puts it, broken up and spread throughout the area as builders sand or used for road repairs. Stafford describes it as having had two massive shoulders of blue-grey rock, 25 feet high, divided by a narrow cleft in which children could hide. It seems extraordinary now that such a notable landmark could have been summarily destroyed.

It had been a significant point on the Bridford/Christow parish boundary and a place of resort on Christow Common. It is a great shame, to put it mildly, that the Teign Valley Action Group was not then in existence to challenge this destruction.

British Geological Survey – Geology of the country around Newton Abbot (memoir to sheet 339 of the BGS 1:50,000 survey). [HMSO 1984]

Colin Burges – A Concise History of the Extractive Industries of Bridford and Christow [Exeter and Teign Valley Railway 1999]

Stafford Clark – Mining and Quarrying in the Teign Valley [Orchard Publications 1995]

CJ Schmitz – The Teign Valley Silver-Lead Mines, 1806 to 1880 [Northern Mine Research Society 1980]

Graham Thompson – A Devon Village: Christow in Victorian Times

Graham Thompson (ed.) – Teign Valley Tales [Teign Valley History Group 2016]

Frank Booker – Industrial Archaeology of the Tamar Valley [David and Charles 1974]

WG Hoskins – Devon [Phillimore 2003]